(C) Kapok Tree Diplomacy. Apr 2012. All rights reserved. Jeff Dwiggins

FREE CONTENT

The Framers for their part did have a lot to say about the delineation of powers in these areas. The Constitution is a good place to start in determining how those powers are enumerated and what limits if any apply to them.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution says:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” (Passed 12/15/1791).

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution says:

“nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” (Passed 7/9/1868)

These amendments lay out the case for citizens’ right to privacy and limits on government instrusion in this matter without spelling out what constitutes “unreasonable.” Thus, if the President can save millions of lives by wiretapping a suspected terrorist under FISA, is this “reasonable?”

The Constitution gives the President the following authority in Articles I and II:

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” (Art. I)

“He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.” (Art II)

So how much power is executive power? How much power did the Founders think this met? In Federalist Paper No. 64, John Jay makes it clear that this power should include

“It seldom happens in the negotiation of treaties, of whatever nature, but that perfect SECRECY and immediate DESPATCH are sometimes requisite … The convention have done well, therefore, in so disposing of the power of making treaties, that although the President must, in forming them, act by the advice and consent of the Senate, yet he will be able to manage the business of intelligence in such a manner as prudence may suggest.” (3/7/1788)

Professor Robert F. Turner expands on these thoughts of the Founders by laying out quote after quote of Founder thoughts on the subject as well as key cases that have come before the Supreme Court. In Barenblatt v. United States 360 U.S. 109 (1959), the Court notes: “Congress…cannot inquire into matters which are within the exclusive province of one of the other branches of the Government.” (2007, slide 64)

In another important case, United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., the decision rendered stated as follows: “Not only, as we have shown, is the federal power over external affairs in origin and essential character different from that over internal affairs, but participation in the exercise of the power is significantly limited … He makes treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate; but he alone negotiates. Into the field of negotiation the Senate cannot intrude; and Congress itself is powerless to invade it.” (2007, slide 45)

Prof. Turner’s point is that the President is perfectly within his Constitutional discretion to do things like order wiretaps on foreign terrorist suspects because this is reasonable first, and secondly it is not an exercise of domestic power but of power in the foreign policy arena (slide 116). Moreover, he feels the Framers statements back him up, and that it is Congress who has broken the “higher law of the Constitution,” not the President (slide 106). If a traffic sobriety checkpoint is reasonable, why not a wiretap that could save millions of lives (2007, slide 93)?

There is also the question of what is “necessary and appropriate force” as referenced in the Sept. 18, 2001 AUMF to prosecute the “War of Terror” (2007, slide 7). Certainly, some intelligence must be necessary and appropriate. Why not wiretaps? Today, the thoughts of the Framers hold true in many aspects as the President is still able to exercise a great deal of discretion in his foreign policy dealings. One should keep in mind that the Framers lived in a much different time and didn’t have the technology we have today.

President Bush took the U.S. to two wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, conducting massive and expensive nation building projects in both. He also played a principal role in furthering the “War on Terror” and bulking up the Department of Homeland Security and the Transportation Security Administration with all of its airport screenings. Congress eventually pushed back when the wars dragged on and the expenses started spiraling upwards.

President Obama ordered the surge in Afghanistan and regularly employs drones to go out and kill terrorists in Pakistan, Yemen and surrounding areas (Singer 2012). Congress is looking for more information on this as well (Singer 2012). Apparently drones are “necessary and appropriate force” to continue to prosecute the never-ending war. But who is complaining besides maybe a few civil rights and news organizations? After all, we’re safe.

The War Powers Act should in theory make Congress a more viable player in foreign policy decisions. The debate over the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea continues to be mired in the wasteland of “advice and consent of the Senate.” Not many major treaties are concluded these days, but regional or bilateral treaties are still concluded regularly by the President. The Framers could probably not have imagined the role that special interest groups, PACs, think tanks, the media and lobbyists play in foreign policy, but today they do play a significant role.

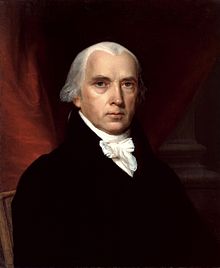

In conclusion, the President still has a pretty strong hand to make foreign policy decisions, though he is restricted in his intelligence collection efforts, perhaps erroneously. Congress manages to make themselves a bigger part of the process than in the days of Washington, Madison and Jefferson. Debate on the issues of privacy and what is authorized and legal under the Executive Clause and “all necessary and appropriate force” will continue for sometime. Congressional pushback has rendered some of the Founders’ thoughts on Executive foreign policy discretion less significant, but not by much.

References

Jay, John. Federalist paper no. 64. 1788 [cited September 16 2012]. Available from http://www.conservativetruth.org/library/fed64.html.

Singer, Peter W. 2012. Do drones undermine democracy? The New York Times Sunday Review, January 22, 2012, 2012, sec Opinions Page. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/22/opinion/sunday/do-drones-undermine-democracy.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all (accessed April 30, 2012).

Turner, Robert F. FISA vs. the Constitution: Why the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act is unconstitutional and how it contributed to the success of 9-11. in Center for National Security Law, University of Virginia School of Law [database online]. October 2007 [cited September 16 2012].

U.S. Congress. The Bill of Rights. in U.S. National Archives [database online]. New York, NY, 1992 [cited April 30 2012]. Available from http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights_transcript.html (accessed April 30, 2012).

Leave a Reply